Deep in the Swiss Alps, next to an old airstrip suitable for landing Gulfstream and Falcon jets, is a vast bunker that holds what may be one of the world’s largest stashes of gold.

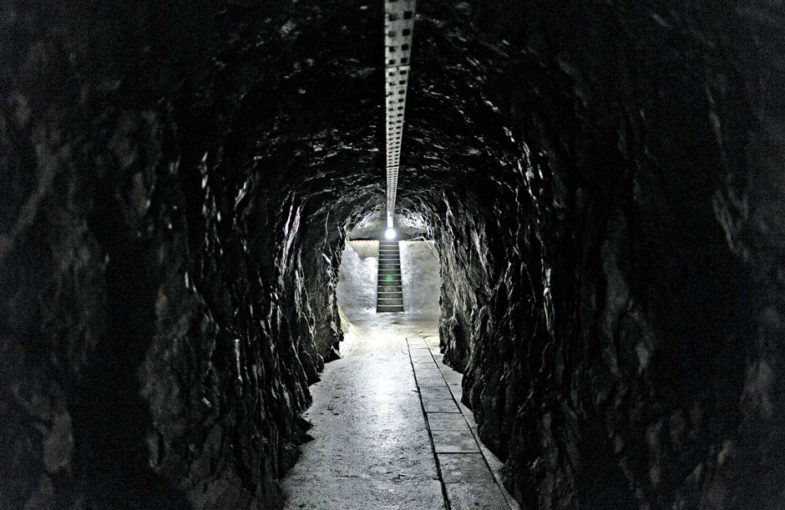

The entrance, protected by a guard in a bulletproof vest, is a small metal door set into a granite mountain face at the end of a narrow country lane. Behind two farther doors sits a 3.5-ton metal portal that opens only after a code is entered and an iris scan and a facial-recognition screen are performed. A maze of tunnels once used by Swiss armed forces lies within.

The owner of this gold vault wants to remain anonymous for fear of compromising security, and he worries that even disclosing the name of his company might lead thieves his way. He’s quick to dismiss questions about how carefully he vets clients but says many who come to him looking for a safe haven for their assets don’t pass his sniff test. “For every client we take, we turn one or two away,” he says. “We don’t want problems.”

Demand for gold storage has risen since the 2008 financial crisis. Many of the wealthy see owning gold as a hedge against the insecurity of banks and a reasonable investment at a time when markets are volatile and bank accounts and low-risk bonds pay almost no yield. It may also be a way to avoid the increasing scrutiny of tax authorities. In high-profile cases, U.S., French, and German prosecutors have gone after citizens of those countries with undeclared Swiss bank accounts.

Demand for gold storage has risen since the 2008 financial crisis. Many of the wealthy see owning gold as a hedge against the insecurity of banks and a reasonable investment at a time when markets are volatile and bank accounts and low-risk bonds pay almost no yield. It may also be a way to avoid the increasing scrutiny of tax authorities. In high-profile cases, U.S., French, and German prosecutors have gone after citizens of those countries with undeclared Swiss bank accounts.

Of the roughly 1,000 former military bunkers still in existence across Switzerland, a few hundred have been sold in recent years, and about 10 are now storage sites holding gold as well as computer data, according to the Swiss defense department.

Few match the opulence of the airstrip setup, whose owner claims to run the largest store of gold for private clients—and the seventh-largest gold vault in the world. Near the runway sits the VIP lounge and a pair of luxurious apartments for clients. The walls of the apartments are lined with aged wood from Polish barns. South African quartzite was chosen for the floors to match the faded gray timber, and the amenities—bathroom mirror, TV screens—can retract into the ceiling, counter, or wall. The owner offers a place for clients to sleep and eat, because “many do not want to leave a paper trail of credit card receipts and passports” at hotels and restaurants.

Some miles away, Dolf Wipfli, the founder and chief executive officer of a different company, Swiss Data Safe, is one of the few operators willing to be interviewed about his business. The gold Swiss Data Safe stores for clients is kept in a mountainside bunker outside the hamlet of Amsteg. On a recent tour, Wipfli wouldn’t disclose the gold’s exact location, choosing instead to take visitors into a room containing computer servers for the other half of his business, providing data backup storage. Wipfli declines to say how much he charges to store gold. The company’s website has versions in Chinese and Russian.

Nor do such companies have to report suspicious activity to Switzerland’s Money Laundering Reporting Office. In the past, submissions to the agency have led the Swiss attorney general to open investigations into corruption at FIFA, the global soccer body, and banking ties to Brazil’s Petrobras bribery scandal.

“The gold trade is a huge part of the Swiss economy,” says John Cassara, a former U.S. Treasury special agent and the author of books on money laundering. “I’m not surprised that there are not more effective efforts in Switzerland to better monitor its misuse. The powers that be don’t want to crack down.” In the first half of this year, 1,357 metric tons of gold—worth about $40 billion—were imported into Switzerland, according to the Swiss customs office, putting the year on course to be the biggest since a record in 2013.

“The gold trade is a huge part of the Swiss economy,” says John Cassara, a former U.S. Treasury special agent and the author of books on money laundering. “I’m not surprised that there are not more effective efforts in Switzerland to better monitor its misuse. The powers that be don’t want to crack down.” In the first half of this year, 1,357 metric tons of gold—worth about $40 billion—were imported into Switzerland, according to the Swiss customs office, putting the year on course to be the biggest since a record in 2013.

The Swiss secretary of state for international finance issued a report in December on safe deposit boxes and the risk that they are abused for money laundering and terrorism. The former army bunkers weren’t mentioned in the report. “We don’t see any tangible evidence of criminality of a systemic nature, but this could be a topic for the future,” says a spokesman when asked about the bunkers.

Of course, there are plenty of legitimate reasons for investing in gold. The metal’s price has risen 25 percent since the end of 2015. The tonnage of gold assets in exchange-traded funds has climbed 39 percent this year, data compiled by Bloomberg show.

Even so, the Financial Action Task Force, an intergovernmental body that sets anti-money-laundering standards, warned in a 2015 report of the risks of gold being used by criminals for financing terrorism or for laundering money. Cassara, the former Treasury agent, says, “Perhaps gold should be subject to currency cross-border reporting.”

Wipfli says Swiss Data Safe, too, scrutinizes prospective clients and will reject those “for whom it doesn’t have a good feeling.” The company accepts corporate clients but insists on knowing who the owner of the company is, he says, a condition that goes beyond the more relaxed federal customs rules that govern Switzerland’s controversial free ports, where art and other valuables are stored.

Wipfli’s company also insists on inspecting goods that come into its bunkers. That, he says, distinguishes it from the no-questions-asked policy of safe-deposit-box companies that have been flourishing in the canton of Ticino, 100 miles south. “We don’t do black-box storage,” he says.

Source: Bloomberg News