Just over 14% of men work part-time in Switzerland, a country with the second highest rate of part-time workers out of all OECD nations. Nine out of ten men would like to reduce their hours at work, according to one study. So why don’t more make this a reality?

Balancing work demands with family or free time can be difficult in practice and tricky to bring up with the boss

(Keystone)

“Lots of men feel responsible for their family’s financial security, they’re worried about their career being affected by their decision and they’re anxious about appearing unmotivated at work,” Jürg Wiler, co-leader of the ‘Teilzeitmann’ (Men Working Part-Time) campaign told swissinfo.ch

Wiler is an advocate for men who want to achieve a bit more work-life balance and says that during the lunchtime events he organises to promote this way of working, he regularly talks to men who “fear stigma in their business and social environment” and who have questions about a “loss of status”.

The campaign, which is a project by männer.ch, the Swiss association of men’s and father’s groups, carried out a study in canton St Gallen in 2011. They spoke to 1,200 men from all walks of life and found that 90% of them wanted to work part-time.

In 2012 they started making role models available – ordinary men who just happened to work part-time, and were happy to speak about their experience to others.

Thomas Stucki is one of them. He’s been in part-time employment since he retrained and studied for a second degree, in social sciences, at the age of 30.

“When I started my university studies, I had to work part-time to earn the money I needed. And from that time on, after the degree and after having studied, I never got back to a full-time job because I saw that this was a good thing for me.”

By the time Stucki neared the end of his course, his wife was expecting their first child. “We didn’t even question that I would work part-time. I wanted it this way and she did too. So, as a couple, we decided to try it.”

For couples such as Stucki and his wife, who works as a child and youth psychologist, sharing the childcare and the responsibility for earning a living was a natural choice.

The father-of-two told swissinfo.ch that he considers himself lucky, as he receives a generally positive response when he tells other people about the family set-up: “I generally meet and know people who share the same values. I’m not so much in contact with classical business people, who might say, ‘oh you’re working part-time, how do you that’, and so on”.

Fears of repercussions in the workplace mean that more men would like to work part-time than the number that do, according to Irenka Krone, a specialist in part-time work at the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO).

“There are many employers, that when men are asking for that [to work part-time] they have the reaction that this person is not really interested in what they are doing…so there is a misperception.”

But Wiler believes that attitudes are changing towards part-time positions for men.

“It seems to be more accepted when men say they want to put in a full performance, but they don’t want to have a workload of 120% or even 140% anymore,” he told swissinfo.ch. “This is something from the generation before, from our fathers.”

By the fourth quarter of 2013, an additional 23,000 men had started working part-time – a 0.9 percentage point increase on the fourth quarter of 2012.

“That’s very important for us…it was a big jump,” Wiler said.

Over the whole year, 2013 saw a slightly smaller increase on the year before.

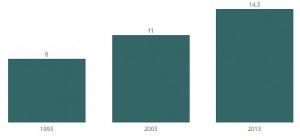

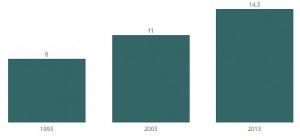

How the average number of men working part time has changed over the past twenty years (as a percentage of all working men).

Source: BFS

Looking at the more long-term figures, it’s clear that part-time employment among men has become more common over the past two decades.

The association’s aim is for 20% of working men to be in part-time employment by 2020.

In comparison, 58.6% of employed women go to work part-time. Since the early 1990s more than half of all women in the workplace have been part-time employees.

Making the business and economics case

Wiler can quote a whole host of studies that show the benefit to business when men work part-time.

He cites German research pointing to a 17% higher productivity among part-time employees and adds that having fewer hours in your contract can lead to lower absence rates, higher efficiency and more motivated staff.

“They [the men] need the acceptance from their employers and from their partners. And for employers it’s important to know that there is a return on investment,” said Wiler.

Krone and her team analysed the situation in Switzerland to come up with possible solutions to common difficulties with part-time work. “We believe that the model of job sharing allows men to continue to make a career while at the same time working on a part-time schedule.”

Referencing Deutsche Bank as a high profile company which has co-chief executive officers, Krone argues that a job share can happen at any level within the hierarchy of a business.

“If you have a position announced on a full time basis and then the role is split between two people, the problem can be a question of salary…if someone has to reduce their salary by 50 or 60%.”

She suggests that while one person works 70% of their contracted hours on certain high level tasks, but shares the very top position with another person, this would allow another employee to work part-time.

Stucki is also well aware that with reduced hours comes a reduced income, and a lower pension.

“It cannot work for everyone from a financial point of view. Even for me and my wife – we have university degrees, we have a good education and had good opportunities – and it’s not easy, “ Stucki said. “I can imagine if you are not in such a good position, it’s not possible.”

“There is a change happening in the mindset of younger fathers…there is a change in progress,” said Wiler, convinced that despite all of these points, attitudes towards part-time work are becoming different among employers and in society.

By Jo Fahy

Source: Swissinfo.ch

Read More »