Origami batteries, could one day power biosensors for use in remote locations, developed by Binghamton University researcher Seokheun Choi.

Origami, the Japanese art of paper folding, can be used to create beautiful birds, frogs and other small sculptures. Now a Binghamton University engineer says the technique can be applied to building batteries, too.

Origami, the Japanese art of paper folding, can be used to create beautiful birds, frogs and other small sculptures. Now a Binghamton University engineer says the technique can be applied to building batteries, too.

Seokheun “Sean” Choi developed an inexpensive, bacteria-powered battery made from paper, he writes in the July edition of the journal Nano Energy.

The battery generates power from microbial respiration, delivering enough energy to run a paper-based biosensor with nothing more than a drop of bacteria-containing liquid. “Dirty water has a lot of organic matter,” Choi says. “Any type of organic material can be the source of bacteria for the bacterial metabolism.”

The method should be especially useful to anyone working in remote areas with limited resources. Indeed, because paper is inexpensive and readily available, many experts working on disease control and prevention have seized upon it as a key material in creating diagnostic tools for the developing world.

“Paper is cheap and it’s biodegradable,” Choi says. “And we don’t need external pumps or syringes because paper can suck up a solution using capillary force.”

While paper-based biosensors have shown promise in this area, the existing technology must be paired with hand-held devices for analysis. Choi says he envisions a self-powered system in which a paper-based battery would create enough energy — we’re talking microwatts — to run the biosensor. Creating such a system is the goal of a new three-year grant of nearly $300,000 he received from the National Science Foundation.

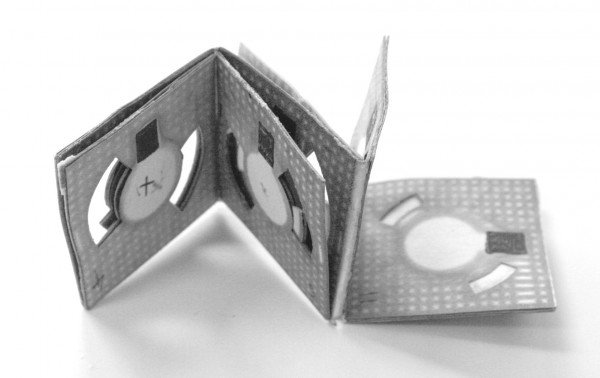

Choi’s battery, which folds into a square the size of a matchbook, uses an inexpensive air-breathing cathode created with nickel sprayed onto one side of ordinary office paper. The anode is screen printed with carbon paints, creating a hydrophilic zone with wax boundaries.

Total cost of this potentially game-changing device? Five cents.

Choi, who joined Binghamton’s faculty less than three years ago as an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering, earned a doctorate from Arizona State University after doing undergraduate work and a master’s degree in South Korea. Choi, who holds two U.S. patents, initially collaborated on the paper battery with Hankeun Lee, a former Binghamton undergraduate and co-author of the new journal article.

Choi recalls an actual “lightbulb moment” while working on an earlier iteration of the paper-based batteries, before he tried the origami approach. “I connected four of the devices in series, and I lit up this small LED,” he says. “At that moment, I knew I had done it!”